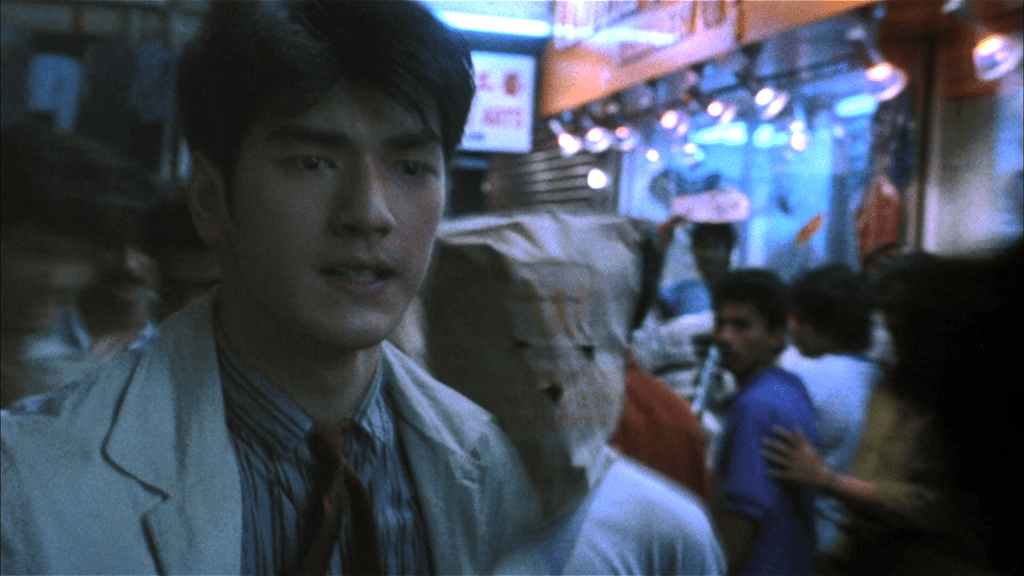

Ivana Wong’s new vehicle (pun intended I’m not sorry) is a genre hybrid following a recently dumped woman trying to find a new path in life. Luckily, there’s a lot more going for the film than simply Ivana Wong’s presence in the lead role. Ostensibly a romantic drama, the film branches out into extended comedic scenes and even incorporates a bit of crime drama toward the climax. While I’ve never particularly been a huge fan of director, screenwriter, and producer Patrick Kong (his cynical penchant for focusing on young people in awful relationship grinds down my patience like sandpaper), he has perhaps found a new footing in focusing on a middle-aged couple. That’s probably not so surprising, given his arguably most interesting film to date was 72 Tenants of Prosperity which also included middle-aged characters.

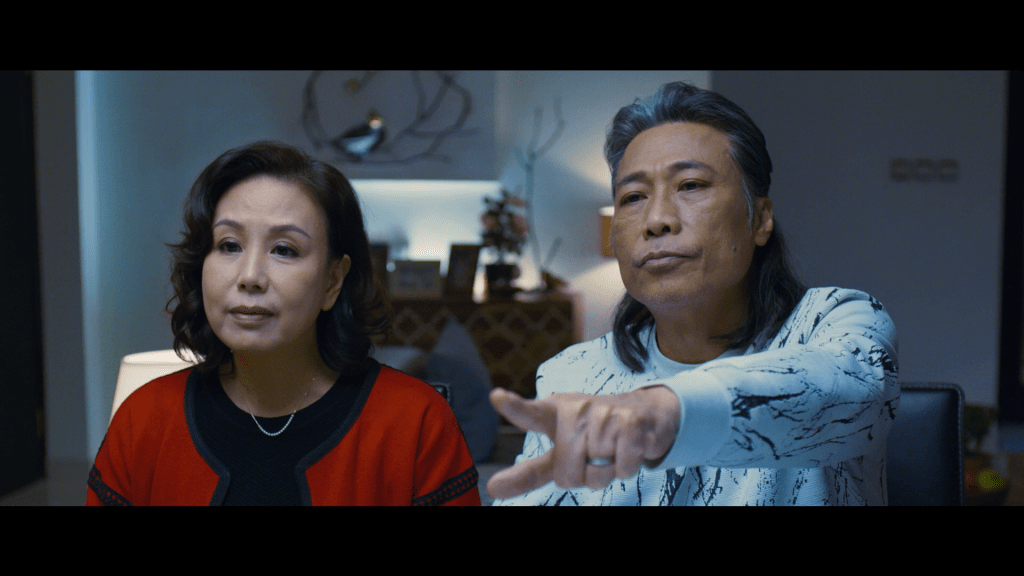

Suki (Ivana Wong) and Chico (Edmung Leung) are in their early 40s and have been together for 7 years, running a business together and edging towards marriage. With matrimony in her grasp, their sauce business attracts the attention of Mainland Chinese businesswoman Kiki (Jacky Cai) who has ulterior motives.

First things first, this is a lighter-themed movie and Ivana Wong always seems to enjoy these roles. As lovely as ever, the now 41 years old Wong has improved her command of the screen and versatility. It’s always a joy to see her in movies, even with the more serious dramatic turns like Ann Hui’s Our Time Will Come. Granted, being only a Category IIA film and a Patrick Kong movie, don’t expect the rest of the cast to always be on Ivana Wong’s level of dialog delivery and emotional display. That’s just how it is, though, it’s a local HK production and no one is going to see these for their believable tearjerking moments.

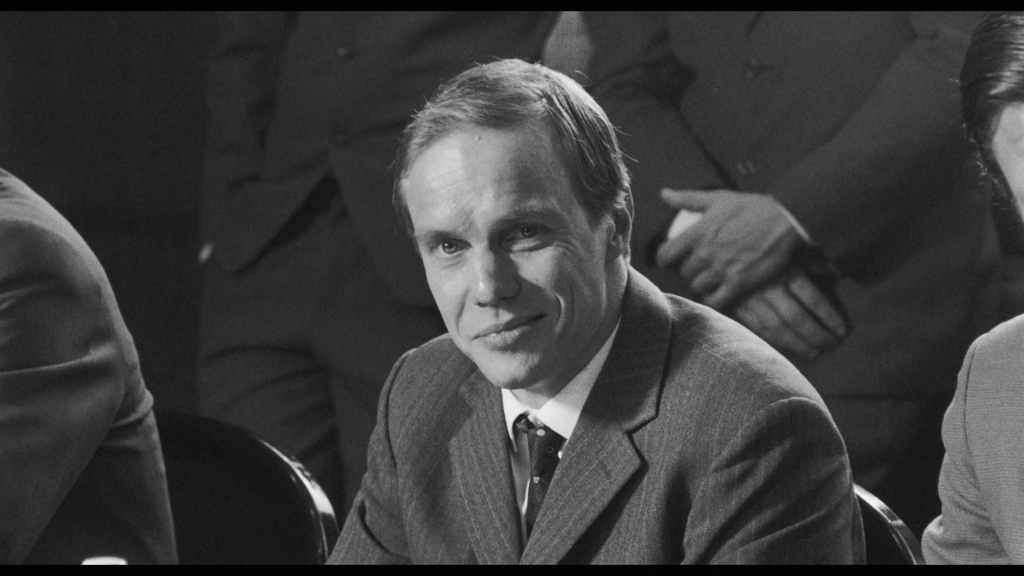

That said, the real pleasant surprise here is the chemistry between Wong and Philip Keung as Manny, the jilted ex-boyfriend of Kiki. Keung here shines in a role that exhibits the same emotional peaks and valleys as Suki, but without progressing into emotional whiplash. Keung is in the most comedic role of the film, with exaggerated emotions juxtaposed with bouts of intense solemnity that seem to imply his character is not necessarily playing with a full deck. His outbursts recall Al Pacino’s Detective Hanna in Michael Mann’s Heat. The way Ivana Wong and Philip Keung play off each other, with her character becoming serious and dignified in response to his character’s brashness and questionable mental stability, is a running joke in the film. Also be on the lookout for a hilarious reference to the 2018 HK film Tracey, also starring Philip Keung. If you’ve seen that, you’ll get the joke.

There are some lines of dialog that might very well be Patrick Kong’s advice to the audience, and it’s not subtle at all, but then, subtlety is hard to come by in Hong Kong features. I mean, Jacky Cai’s Mainlander character is an obvious scheming villain. Could it be a political jab of sorts? I certainly got a kick out of it. I won’t go so far as to say there’s truth to the portrayal, because I don’t want to get sued, so instead I will say that I enjoy when a film like this dabbles in realism.

Still, The Calling of a Bus Driver is certainly a step up from Patrick Kong’s other scripts and films. Increasingly towards the end, the film’s moving between genres becomes clearer, with a segment on Wong’s bus concerning a pregnancy and an argument resembling a Mexican standoff, before going back into relationship drama and then finally a foray into crime drama. Does the film shift as deftly between genres as, say, Robin Campillo’s Eastern Boys? Definitely not, but the film comfortably settles into each genre before picking back up again. If this is what Patrick Kong is capable of, I hope he stays the course

4/5

The Calling of a Bus Driver

105 minutes

2.35:1 AR

In Cantonese and Putonghua with English subtitles

Written/dir. by Patrick Kong

Cinematography by Yip Shiu Kei

Hong Kong production

Released 14 November, 2020

Blu-ray disc from Panorama

You must be logged in to post a comment.