The Gwangju Uprising occurred on 18 May 1980 and was a focal point of Korea’s democratization; A Taxi Driver was set during that day. 1987: When the Day Comes takes place during the lead up to the June Struggle, which lasted from 10 June 1987 to 29 June 1987, and resulted in the end of Chun Doo Hwan’s regime. The Gwangju Massacre led to an increasing number of university students becoming democracy activists and protest for democratic reforms throughout the 1980s. The military dictatorship, of course, wasn’t having any of it and branded any government critics “subversives,” “traitors,” “North Korean spies,” etc, to justify extrajudicial killings of dissidents. 1987 is another Korean film tackling this history and dramatizes events when necessary but is based more or less on real people, although unlike A Taxi Driver, 1987 is far more respectful to the history and people who shaped Korea’s progress toward political reform.

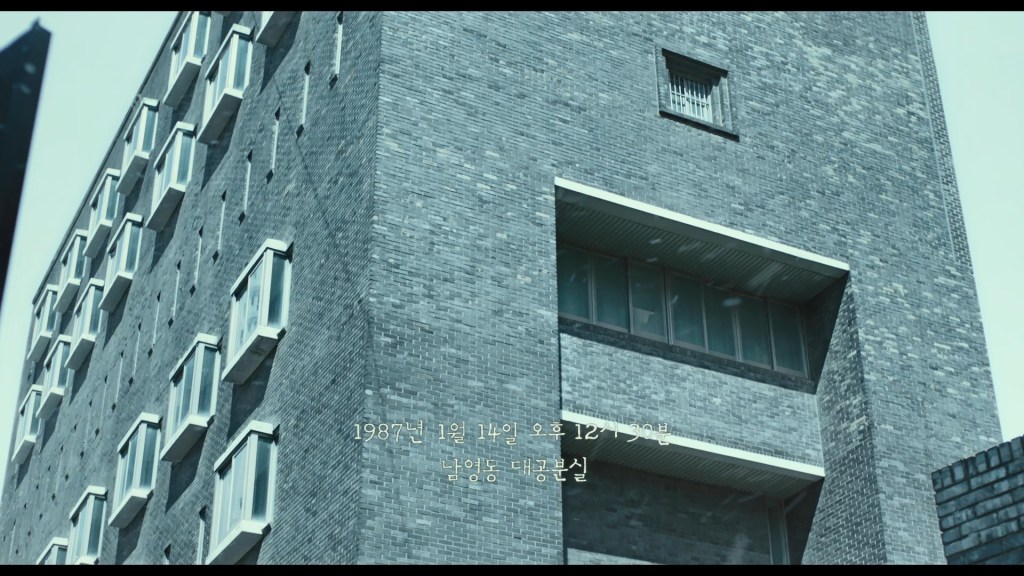

1987 opens on 14 January 1987, in the immediate aftermath of Park Jong Cheol’s murder by the Anti-communist Division stationed in Namyeong-dong, Yongsan-gu, Seoul. Park was a real-life student activist galvanized by the Gwangju Massacre. He was arrested during an investigation and tortured for information regarding the whereabouts of fellow activists. Refusing to yield after multiple waterboarding sessions, the Anti-communist Division tried water cure instead and drowned him in a bathtub while mockingly singing the Korean national anthem. The division attempts to initiate a cover up by first calling a doctor to resuscitate him, and when this fails they resort to attempting to rush a cremation before notifying Park’s family. This backfires when prosecutor Choi Hwan notes how suspicious (and illegal) this is and refuses to sign off on the cremation.

From this point, the film begins a deft mix of historical drama and political thriller. The mix of fictional characters and characters based on real people is commendable. The head of the Anti-communist Division, Park Cheo Won, is dedicated to eradicating opposition to the political regime. What’s interesting here is that the film doesn’t attempt to humanize him or sympathize with him or his zealotry, but does provide a glance at his complexity. He is a villain, for sure, but he escaped from North Korea. It’s strongly hinted that his increasingly erratic statements about protestors and actions geared toward “wiping out commies” stem from a post-traumatic stress disorder due to the atrocities he witnessed and survived in the North, but the film recognizes that his fear of evil does not excuse his own evil acts.

There’s plenty of room to relate this to all manner of political analogues: the Kuomintang initiating the White Terror in Taiwan after the 228 Incident, for one. From 19 May 1949 to 15 July 1987, the KMT murdered or disappeared at least 30,000 Taiwanese dissidents with the excuse that the goal was to eradicate communist sympathizers. The oppression of Palestine by Israel is often defended with citations of a unique need for proactive security because of the Holocaust. In the US, the Red Scares and the vilification of the the Civil Rights and anti-war movements are still felt today, where conservative quarters continue to suggest that even the Kent State Massacre was justified because of alleged communist ties.

Park Cheo Won’s character is perhaps the most central of characters, by virtue of the ever-watchful eyes of his Anti-communist Division and the fact that his playing loose with law has far-reaching consequences for almost every other character. His characterization is particularly noteworthy because despite his self-assurance and statements of only doing what’s right in the interest of national security, he is more than willing to fabricate evidence of communist ties when his subordinates murder people who have turned out to be innocent. He also does not hesitate to order the destruction of records when he worries about their discovery.

Kim Yoon Seok’s performance has just the right amount of disturbing. His scenes are mainly medium closeups and extreme closeups that center his emotionless gaze. His only concerns are killing government critics and saving his career after he kills one too many people; he convinces two lackeys to take the fall for the murder of Park Jong Cheol to take the heat off himself. I’m reminded of Max Hubacher’s spectacular performance in The Captain, a German film about war criminal Willi Herold who, after deserting from the German Army, began impersonating a Luftwaffe officer and ordered the mass execution of deserters at Aschendorfermoor prison camp.

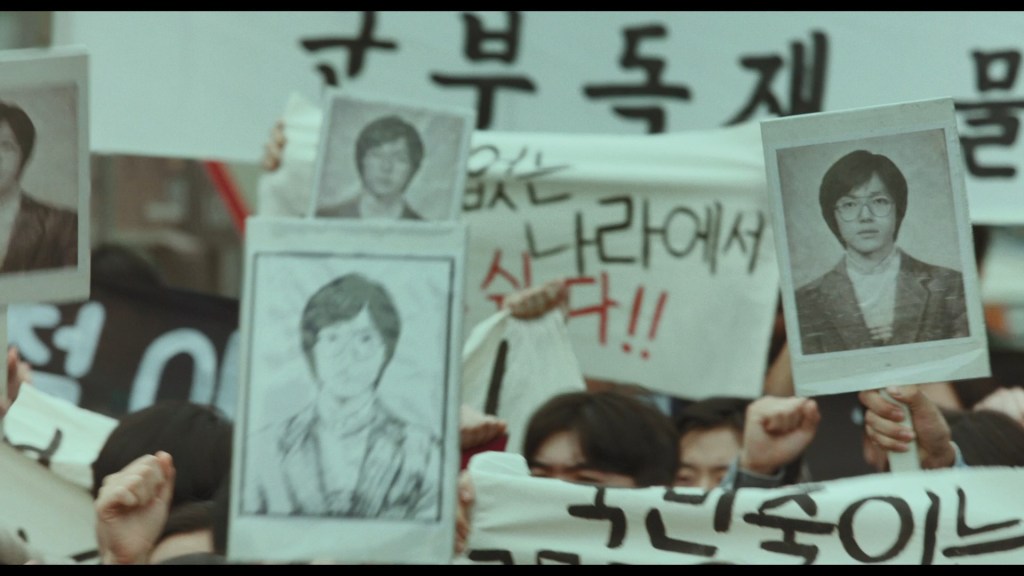

The film makes a great effort to show that this wasn’t a case of a single person toppling a corrupt authority. Mass demonstrations were important, but they fed off the reports from journalists like the character Yoon Sang Sam who refused to follow military-imposed censorship guidelines. His own tenacity for justice was partly fueled by his witnessing Choi Hwan’s arguments with police as well as the military’s rough treatment of Park Jong Cheol’s family, in addition to government officials changing their stories several times when giving press conferences about Park Jong Cheol’s death. Everything bounces off each other like some sort of volatile pinball machine and the film never becomes a mess with all the details to follow.

We do not get such heightened intimacy with the camerawork for other characters, and thankfully so. After being pressed so forcefully close to Park Cheo Won, the other characters’ scenes give us room to breathe with medium and wide shots that still provide glimpses of their personal lives. Mostly, the camera only intrudes closer when the other characters are interacting with each other. The outdoor shots, in particular, offer a stunning display of virtuoso wide shots and crane shots.

Han Byung Yong works at the prison where a number of activists are held, and works to relay messages between the ones locked up inside and the ones who remain hiding on the outside. Yeon Hee, a fictional character, is Han Byung Yong’s niece and is fleshed out greatly. She’s into the currently popular music, studies hard, banters with her best friend, and eventually paves the way for the audience to be introduced to Lee Han Yeol, whom she crushes on after he intervenes to save her from corrupt riot police. Surprisingly, she never becomes subservient to his narrative despite his importance.

That the film went this route of showing her as an average school girl is admirable, because it could have easily made this about a fictional character who rises to the challenge to be a hero, but the reality is not everyone is meant to be grandiosely heroic. Sometimes, a person’s contribution is small, but even a puzzle is incomplete without the tiniest piece. The best part about the more personal scenes involving her is that the music keeps mainly to an orchestral score when it could have tried to charm its way into hearts with Korean ballads from the 80s. There are so many smart decisions made here that a lesser film would have rejected.

Lee Han Yeol was another real-life figure and like Park Jong Cheol, a university student who became an activist. While studying at Yonsei University, Lee took part in the 9 June 1987 demonstration. Police quickly began firing tear gas into the crowd and when they dispersed, an officer deliberately aimed at the back of Lee Han Yeol’s head as he was fleeing and fired a tear gas grenade. His skull was fractured and he died 5 July 1987, after newly-elected President Roh Tae Woo issued the June 29 Declaration, promising democratic reforms. In the film, it is his blossoming relationship with Yeon Hee that drives her to risk her safety to help the pro-democracy movement, and in a way, it’s because of this that Yeon Hee’s character shows the most growth throughout the movie. Everyone else has their convictions and beliefs already, and they stand firm in them, whatever they are, but Yeon Hee comes into her own as painfully and reluctantly as any student who had never been politically active before could be expected to. For a Korean blockbuster, this attention to detail and level of realism is rare.

Going back to my comparison with A Taxi Driver, 1987 is its polar opposite in tone. There are no one-liners or monologues insulting the audience’s intelligence here. No one narrating their feelings before they are seen and astoundingly, no overwhelming score to cue you in to the emotional stakes. Despite being slightly over 2 hours, this is a fast-paced film that the director, Jang Joon Hwan compared the structure of to a relay race. That’s definitely an apt comparison. Basically, we follow a character do something and then we swap to another character as the general consequences of the previous action influence the next action for each character.

If A Taxi Driver prefers convenient sensationalism, 1987 cherishes cohesive characterization. The film gets so much right and very little wrong, especially with regards to tone. This is a film that not only cares about but also respects the people whose stories it’s telling, and avoids cheap theatrics. Because there is such a large number of characters, the film unapologetically rewards attention and concentration, and this is a major step in the right direction for commercial Korean cinema. I’m still looking for an excuse to watch this again instead of conquering the pile of as-yet unwatched movies still accumulating in the corner.

4.75/5

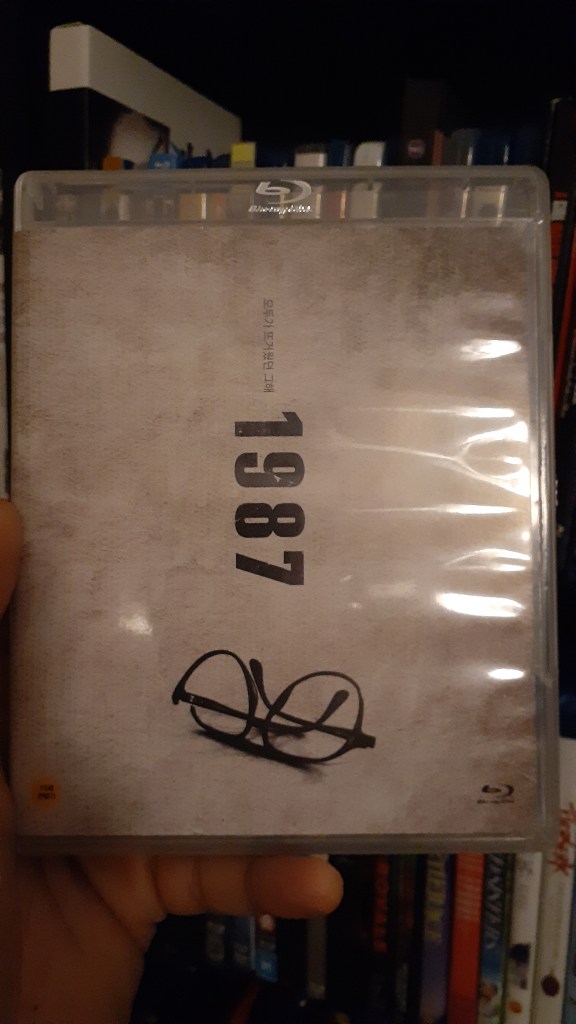

1987: When the Day Comes

129 minutes

1.85:1 AR

In Korean with English subs

Dir. by Jang Joon Hwan

Cinematography by Kim Woo Hyung

Released 27 December 2017

Korean production

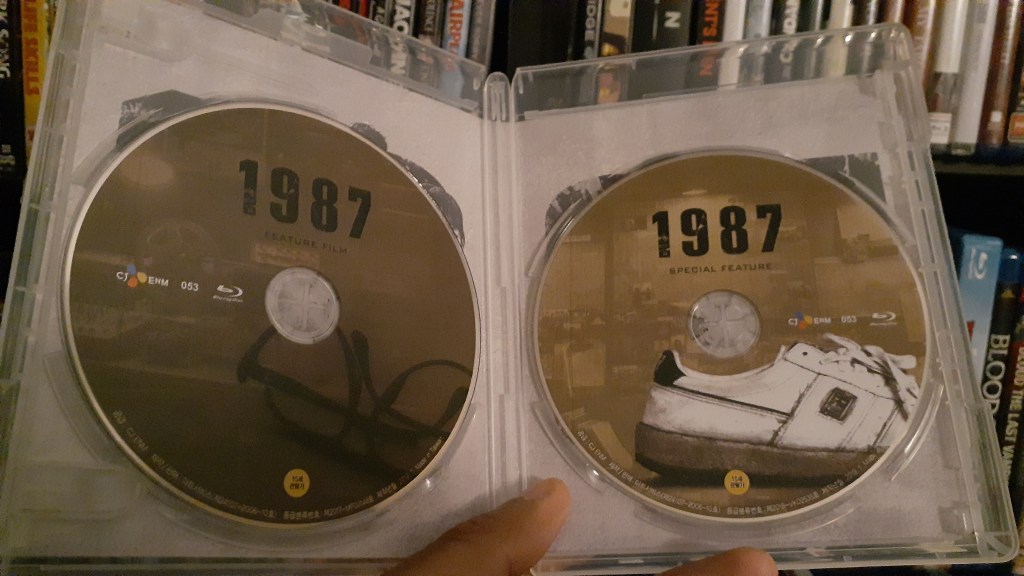

Blu-ray Disc from CJ Entertainment

You must be logged in to post a comment.