This review contains spoilers and references to suicide.

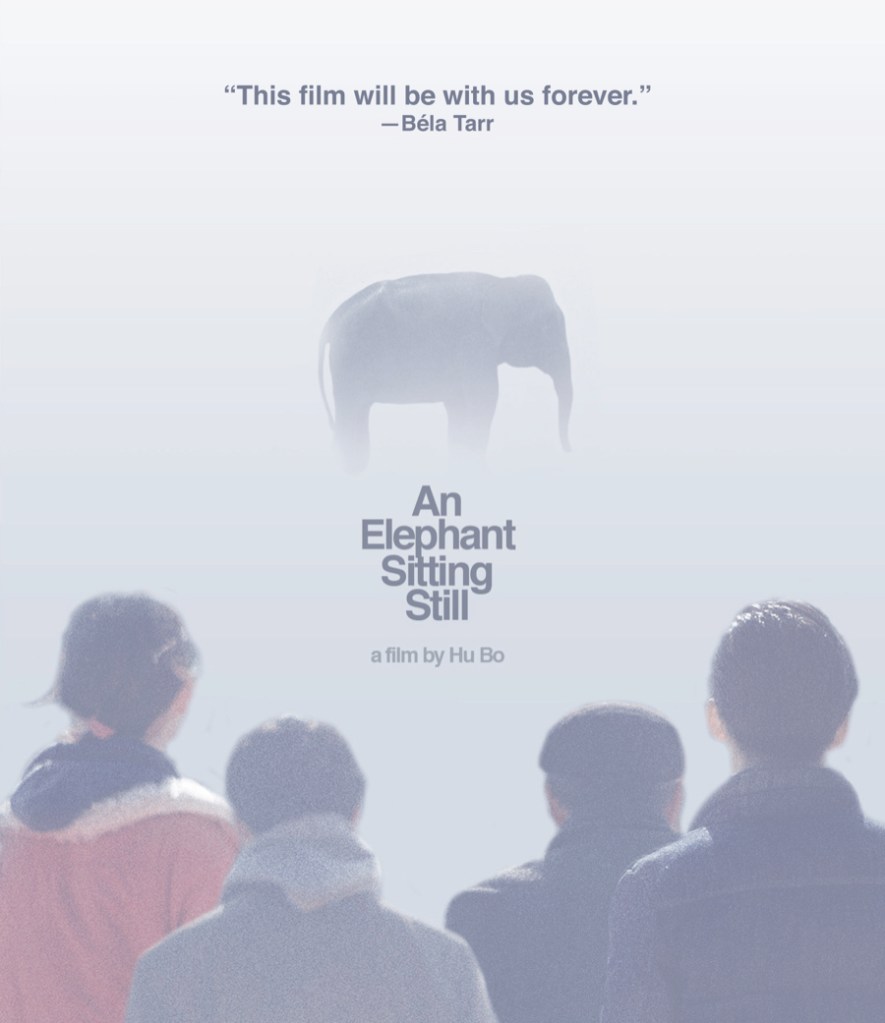

Photos courtesy of US distributor KimStim.

It is impossible to talk about An Elephant Sitting Still without discussing the subsequent suicide of its writer/director, Hu Bo, at age 29. His first and last feature-length film, An Elephant Sitting Still represents a remarkable artistic achievement and an overwhelming tragic loss. Reportedly under stress exacerbated by repeated threats from his producers, Liu Xuan and Wang Xiaoshuai, to cut the 4 hour film to 2 hours or less, Hu Bo killed himself shortly after he finished editing the film. Much like Sarah Kane’s final play 4.48 Psychosis, it is incredibly difficult to not see pieces of the work – if not the whole of it – as the artist’s self-written epitaph or death poem. A bleak depiction of life where the small bursts of contentment, not even happiness, are seemingly also tinged with a fatalist resignation, the film, like Sarah Kane’s swan song, is at once both defined by and resists the trappings of its depressive content. KimStim deserves far more credit than I can give them for being brave enough to release this domestically.

Yu Cheng has just finished having sex with a woman and is smoking a cigarette while looking out the window of the apartment they’re in. The woman mentions that her husband talked about going to the same zoo in Manzhouli to see the elephant that Yu Cheng apparently brought up during pillow talk; an elephant that does nothing but sit on the ground all day, every day, without any movement. The woman orders Yu to “get lost” but he is trying to arrange another meet. The woman’s husband eventually comes home and turns out to be Yu’s best friend. Yu hides in front of the bedroom closet. Upon finding another man’s shoes in his apartment, suspicious of his wife’s excuses, the husband goes to the bedroom and finds Yu. Without a change in facial expression, Yu’s best friend asks Yu if the shoes are his, and after Yu answers to the affirmative, Yu’s friend simply closes his eyes, clenches his jaw, rubs the bridge of his nose, rushes towards the balcony, and jumps out the window to his death.

Wei Bu has fashioned himself a makeshift weapon out of tape and paper in the shape of a rod. His father is hurling abuse through the bedroom door before Wei comes out to eat a meager breakfast with only the slightest acknowledgement of his parents; his father is already drinking liquor. His mother can’t find her gift card to go out shopping, while his father is screaming wild accusations before ordering Wei to leave home. Wei heads to school while engaging in an act of petty vandalism on the way.

Wang Jin, an elderly man, is being lectured by his son about the need for Wang to be put in a home. Wang’s daughter-in-law is present but dressing her daughter for school. The son seems most concerned with creating more space for his daughter in the small apartment, but the apartment is actually owned by Wang. Wang’s solace is his dog, whom he dotes on. During a morning walk, Wang’s dog is attacked and killed by a neighbor’s dog who escaped from its leash. The owners had previously run into Wei Bu asking if he had seen their dog. Wang is refused compensation by the owners because he can’t prove it was their dog that killed his. Alone now, Wang collects his granddaughter and simply wanders, determined not to go into that care home his son wants to place him in.

Wang Jin and Wei Bu live in the same complex, but do not greet each other. Strangers despite their proximity. Wang and a schoolmate walk together before stopping to show off their weapons for dealing with the school bullies; Wang’s baton and his friend’s handgun. It belongs to his father. Wang’s friend points the firearm at his own temple and smiles before Wang takes it and places it back in the friend’s bag. Desperation.

Huang Ling is at home, trying to tell her mother about their toilet leaking again only to be ignored. When she finally wakes her mother up, her mother complains about Huang Ling crushing the birthday cake her mother bought for her, except that the cake box was already shown to be crushed. Much like with trying to explain the leak in the toilet, Huang’s protestations of innocence are ignored by her mother, who eventually merely goes back to sleep.

Wei Bu arrives at school and a bully accosts him, demanding Wei buy the bully a new phone to replace the one Wei stole. Wei insists he had nothing to do with it. Wei later walks into class and sits down but his chair collapses under him. The entire class – except for Wei’s friend from earlier – is looking back at him and laughing. He has likely been bullied for some time now.

Across town, Yu Cheng is meeting with the now-widow of his best friend; Yu insists that he is not guilty of anything and that his best friend’s suicide was his own choice. Yu and the widow argue about who is truly at fault, but the widow blackmails Yu into speaking with his dead friend’s mother, otherwise the widow will tell her departed husband’s family that Yu pushed him from the balcony.

Wei Bu and his friend encounter the bully again, this time in a stairwell. Wei is stoic until the bully starts insulting Wei’s father. The bully demands the pair kneel and sing a lullaby (kneeling is generally considered an act of submission and humility in China) but Wei refuses. After the bully insults Wei’s mother, Wei tries to walk away but the bully grabs him. In the short scuffle, the tape-baton falls from Wei’s bag and the bully spots it on the floor, surprised by the implication that Wei was planning to defend himself, he threatens Wei’s life because of it. Wei pushes the bully down the stairs and then runs away, seeing the bully is unconscious with a head wound.

Yu Cheng gets a call from his mother. His younger brother was pushed down a staircase at school and is in the hospital in critical condition. Coma. The head injury might be fatal because of swelling in the brain.

Huang Ling (who attends the same high school as and is acquainted with Wei Bu) meets with the school’s deputy dean. The dean has been pursuing her for a while, and she has reciprocated the attraction. Problems arise not long after when the two meet in a coffee shop. Wei Bu is outside watching them through the glass. The dean had previously berated Wei Bu as a going-nowhere-loser. Yu Cheng happens upon Wei Bu standing outside, no idea who he is. They peer inside the coffee shop from across the street before Wei Bu writes a note and leaves it on the window (for Huang Ling or the dean?). The two see a person flash by the glass and hear the thud from his placing a piece of paper on the window. Huang Ling walks out of the coffee shop to investigate. She and the dean eat together.

Yu Cheng meets his mother at the hospital. She angrily demands he find the boy who pushed his younger brother. Her verbal abuse recalls Wei Bu’s father. She insists that Yu enlist his gang to enact vengeance.

Huang Ling and the dean meet again. Other students suspect the relationship. A video of them together is being shared online and in group chats. The dean blames her for ruining his life. Her mother finds out and kicks her out. She has nowhere to go and so accompanies the equally aimless Wei Bu.

This is how it begins, and this is only halfway through the 4 hour masterpiece. The score is sparse; it shifts between folk-tinged acoustic guitar and a synth-driven motif dominated by a subtle drones that carry a simple melody. Photographed by cinematographer Fan Chao in a series of meticulous, immaculately composed long takes that alternate between deep and shallow focus, this film takes all the time it needs to tell its story of isolation, abuse, and hopelessness, but also resilience. The fact that it was shot full screen, a format that in the age of widescreen tends to evoke a claustrophobic closeness, means many of the compositions are medium shots (often tracking from behind the characters), closeups, and medium closeups. This is by no means a showcase for widescreen views of buildings in a Chinese city or nature. These characters might be aware of their meager lot in life, but they are still trying to find meaning. Maybe it’s a last stand of sorts. The characters, through their own paths, come across information or flyers about an elephant in a zoo in Manzhouli that sits still all day and does nothing else. For their own singular reasons, they all decide to take the journey to see it. But they remain separate, for the most part, until the very end. These characters exist in the margins of Chinese society and have been abandoned by their families and loved ones, and going to Manzhouli represents them in turn abandoning their lives. There must be something better than what they have. Somewhere inside them, despite their massive alienation, there is an inkling of optimism.

Manzhouli is a city in China (specifically Inner Mongolia) which borders Russia. The film itself is set in Jingxing County, Hebei Province, in North China. Hu Bo himself was born in Jinan, Shandong Province, East China although he had apparently been based in Beijing since attending the Beijing Film Academy. An Elephant Sitting Still was adapted by Hu Bo based on a novella in his short story collection Big Crack (also known as Huge Crack). I don’t know exactly how to view the film. As a protest against the failings of Chinese society? An indictment of the Chinese Communist Party for their inability to truly care for the citizens of the country? A cry for help from someone making his suicidal intentions known onscreen? A plea for everyone to try to make connections with each other, lest the people we pass by every day end up slipping through cracks before our very eyes? Maybe it was an author trying to bestow a final gift to the world and show that people should remain hopeful even if he could not. Perhaps it’s a combination of all of them, in differing amounts for each. Either way, the solemnity is palpable. It’s a great film and I don’t have to understand it completely to recognize that. Hu Bo could have gone on to make more great feature-length films, but unfortunately we only have this, three short films, and his three novels. At least we have something from him.

20 July 1988 – 12 October 2017

5/5

An Elephant Sitting Still

234 minutes

1.78:1 AR

In Mandarin with English subtitles

Written/dir. by Hu Bo

Cinematography by Fan Chao

Released 14 December 2018

Chinese production

Blu-ray Disc from KimStim